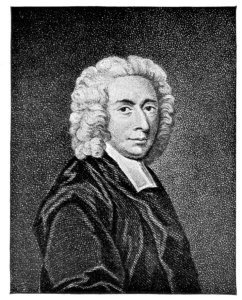

This is my final installment on a series of 3 posts on the life and hymnody of Isaac Watts, the "Father of English Hymnody." I find it particularly interesting in this segement how progressive Watt's writing was and how as pastors and song leaders began to integrate his hymn texts in both casual and formal settings (as sung hymns) they were met with staunch persecution.

This is my final installment on a series of 3 posts on the life and hymnody of Isaac Watts, the "Father of English Hymnody." I find it particularly interesting in this segement how progressive Watt's writing was and how as pastors and song leaders began to integrate his hymn texts in both casual and formal settings (as sung hymns) they were met with staunch persecution.- - - -

Despite the “Calvinistic” theology that went into his hymns, many of his songs were accepted and embraced by all cultures and denominations. His hymns were definitely the most popular hymns of the day. They were so well and loved that they were heard sung everywhere, even on the streets of London. Farmer, Ebenezer Holman would pause from his labor in the fields on a daily basis to lead his men in the hymn “Come all Harmonious Tongues.” In witnessing the scene Paul Manning writes:

He lifted his spade in his hand, and began to beat time with it; the two laborours seemed to know both words and music, though I did not…. Somehow, I think that if I had known the words, and could have sung, my throat would have been choked up by the feeling of the unaccustomed scene.This kind of “recreational” singing of hymns fell under harsh criticism by pastors like Charles Chauncy , pastor of First Church in Boston. He was sharply opposed to the emotional and common application of hymnody in every walk of life. Watt’s hymns even became popular in the African American tradition. African Americans would often use Watt’s text and then set them to their own rhythms. Other denominations who didn’t agree with his theology would take many of his hymns and simply edit them to fit into their theological perspective. The Unitarians were known to take many of his hymns and carefully doctor them, removing any trace of the name of Christ.

Watt’s popularity in the American colonies exploded on the heels of the first and second great awakenings. The first great awakening was launched and sustained primarily through the ministries of two men, evangelist George Whitfield and theologian and pastor Jonathan Edwards. Whitfield was a captivating speaker who awakened curiosity within inventor Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was so impressed by Whitfield’s preaching that he came away from Whitfield’s message believing that his messages could be heard by over 30,000 people at one time. Jonathan Edwards was both a pastor and theologian. He is also recognized as the first president of Princeton University. One of the greatest reasons these influential leaders promoted the songs of Watts wherever they went was because he was theologically united with them in their love for Calvanistic theology. An illustration of this can be seen in Whitefield’s rejection of Wesley hymns. “When Whitefield came preaching to the American colonies in 1739, he brought with him Wesleyan hymns. When he protested the Wesley’s Arminian stance, he abandoned Wesley for Watts.”

Another reason that Watts hymns were so popular in the church of the Americas was because in America the church was in a difficult time of reformation and persecution. Watt’s fresh approach to hymnody and inspiring settings fueled peoples desire to stand up to the hypocrisy and tyranny of the corrupted church. One example of this early persecution is seen in this report of what happened in 1771, when a small Baptist congregation began adapting to the practice of singing.

Brother Waller informed us…. [that] about two weeks ago on the Sabbath Day down in Caroline County he introduced the worship of God by singing…. The Parson of the Perish would keep running the end of his horsewhip in Waller’s mouth, laying his whip across the hymn book, etc… When done singing [Waller] proceeded to prayer. In it he was violently jerked off the stage; they caught him by the back part of his neck, beat his head against the ground, sometimes up, sometimes down, they carried him through a gate that stood some considerable distance, where a gentleman [the sheriff] gave him… twenty lashes with his horsewhip…. Then Bro. Waller was released, went back singing praise to God, mounted the stage and preached with a great deal of liberty.This example of the religious persecution of the day portrays some of the climate in which his hymns so radically lit within the people a desire to sing praise to God in a whole new way. In many ways Watt’s legacy of great hymns have been a more lasting influence upon the church and it’s theology than any great speaker or preacher. One of the hymnals that was written during the second great awakening was Ashel Nettleton’s, Village Hymns for Social Worship. In this hymnal Nettleton featured close to 50 Isaac Watts hymns. In the preface of Nettleton’s hymnal he writes:

With great satisfaction and pleasure have I often heard the friends of the Redeemer express their unqualified attachment to the sacred poetry of Dr. Watts. Most cordially do I unite with them in the hope that no selection of hymns which has ever yet appeared may be suffered to take the place of his inimitable productions.This hymnal was considered by some as the “most evangelistic” hymnals ever produced.

The hymns of Watt’s won the attention of many great people. One of Isaac Watt’s greatest fans was Benjamin Franklin, who was responsible for publishing his Psalm paraphrases in 1729. Fanny Crosby, the most prolific American hymn writer of all time was converted when listening to the Watts tune “Alas and Did My Savior Bleed.” Charles Wesley himself, said that he would have given up all the hymns he wrote, if God would have allowed him the write the words of this most famous hymn of Isaac Watts:

When I survey the wondrous Cross

On which the Prince of Glory died,

My richest gain I count but loss,

And pour contempt on all my pride.

Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast,

Save in the death of Christ, my God;

All the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them to His Blood.

See, from His head, His hands, His feet,

Sorrow and love flow mingled down!

Did e’er such love and sorrow meet,

Or thorns compose so rich a crown?

Were the whole realm of nature mine,

That were an offering far too small;

Love so amazing, so divine,

Demands my soul, my life, my all.

This hymn which was inspired by Watt’s reading of Galatians 6:14 was the one that Matthew Arnold named the finest hymn in the English language. Hymnologist John Julian declares that it must be classified with the four lyrics that stand at the head of all English hymns.

Isaac Watts life finally gave in to his life time of sickness and frailty. He passed away on November 25 of 1748. He was buried at Bunhill Fields, London, near the graves of John Bunyan and Daniel Defoe. A monument to his memory was placed in Westminster Abbey, the highest honor that can be given an Englishman. Perhaps as an even greater monument in his honor are the many hymns that Christians have been singing and will continue to be sing for generations to come.

1 comment:

A good friend shared a clarification with me that I would like to pass on.

"In a couple of places you implied that Watts wrote music, and he was a "text-only" guy, as far as I know... Watts expected that his texts would be fitted to the standard psalm-tunes of the day, and that is perhaps the biggest reason why he wrote hymns in very few poetic meters (in this sense he was conservative)."

I appreciate the clarification.

Post a Comment